A deep dive into techno history – an interview with Ken Ishii

Ken Ishii, one of Japan’s techno pioneers returned to Budapest in February to celebrate the 30th anniversary of his career with a special DJ set and I took this opportunity to sit down with him before the show to talk about his music, his career, his roots and about the history of the Japanese techno scene.

What were your first musical influences and how did you turn towards electronic music?

I think it was Yellow Magic Orchestra, probably in 1980, when I was 10. Actually from the time when I was 8 or 9 YMO was huge in Japan and I first heard their music in elementary school, when at the annual gymnastics festival they played Rydeen by Yellow Magic Orchestra for the running competition. So that was the first time. Until then I only heard normal “tv music”, music for children or songs animes and I noticed the difference and that it is more electronic. So, after that I asked my parents about YMO and also some of my older friends had records from them, so that is how I started to listen to music by my own intention. It was pretty early.

And then later on you turned more towards Western electronic music?

Yes, after YMO I started to listen to more electronic music. Of course there was Kraftwerk and some other German bands from the same period and also electro pop, like Human League and even some pop bands. And Devo and of course New Order, Depeche Mode and some similar bands. When I was a teen I was more looking back into what existed already, discovering old bands and music, but then I finally encountered some new music. Which was Detroit techno. I already listened to some early deep house and Chicago house stuff, wich was yeah… something new alright, but it was Detroit techno that changed me. For me it was like… that’s it, this is electronic music. And I also discovered the whole DJ culture and dance music scene. It was totally new for me and I felt that this is really something that I can love. It was in the late ’80s, around ’89 or ’90.

So, basically it was early Detroit techno that really got me into electronic music and also into doing music by myself. At that time, when I was 19, during my first year in university was when I started to practice DJing and also making music with some simple gear.

Then you had your first releases in 1993 and looking back at it, it seems that everything happened at once and within a year you was all over the place, having releases out at some of the biggest techno labels at that time, including R&S, ESP and Plus 8. How it all happened so suddenly?

Well, it was really drastic. I was really just a simple student, who was dreaming to be an international artist, but at that time in Japan the techno scene was so small, I think there was only one, tiny techno club then, with a capacity of maybe a few hundred people. But I was always checking British and American magazines about the latest dance, house and techno music and it was also at that time when some import record stores opened in Shibuya and so on. It was kind of a good timing for me as I was able to check new records every week and even though no local media covered these kinds of music, I could be up-to-date thanks to these record stores and overseas magazines.

Then by the time I was making my own music for about two years I started to feel that I am doing something good, doing tracks that are actually good. And I had one friend who was also into this sort of music and was also practicing DJing and I showed him some of my tracks and he said “Oh, it was not bad, why don’t you approach some record companies?” Ad I was like “Oh? Really? Well, ok!” And at that time my most favorite label was R&S from Belgium and they were also the biggest techno label then, so I thought… “Why shouldn’t I approach the top one first?”

So, I sent them a cassette tape and already after the first tape they wrote me back. I received this envelope, with a letter and they said that they were curious about my music and wanted to listen more of it. I was like… what? Really? So, I sent them a few more tracks, I think two more tapes? And then they replied again, saying that they decided to release my music. It was actually really simple, with just 2 or 3 tapes and letter exchanges. So, they sent me a contract by FedEx and I have never even seen a FedEx envelope till then. And my mother was there when I received it and was really surprised, asking “What is this? Is it really from Belgium… from Europe!?”

So, I sent them a cassette tape and already after the first tape they wrote me back. I received this envelope, with a letter and they said that they were curious about my music and wanted to listen more of it. I was like… what? Really? So, I sent them a few more tracks, I think two more tapes? And then they replied again, saying that they decided to release my music. It was actually really simple, with just 2 or 3 tapes and letter exchanges. So, they sent me a contract by FedEx and I have never even seen a FedEx envelope till then. And my mother was there when I received it and was really surprised, asking “What is this? Is it really from Belgium… from Europe!?”

I felt that “I made it!” I was 21 around that time and about half-a-year after I received the contract, the first single was released. So, it was really drastic, that a local student suddenly became an international recording artist.

And the other labels, like Plus 8 approached you after that?

No, actually around the same time I got the contract, I started sending music to other labels as well, saying “I am already in contract with R&S, so please give a listen to my music.” And my EPs on different labels were eventually released almost at the same time, within two or three months. I did not expect the timing to be like this, but actually it had a good impact in Europe.

In the first few years you was using several different aliases: Flare, FLR, UTU, Yoga and Rising Sun. And the sound was sometimes quite different, the Flare releases had an experimental dance music feel, while Rising Sun and Yoga were more atmospheric. Did you started to use these names to clearly separate these different sounds?

Actually everybody used to do this around that time, it was completely normal and I was young and just thought it is cool to have some many names. But it was also because I felt that I had several different styles. One that was a bit more straightforward to dance to, and also some stuff that was more experimental or atmospheric as you said and I thought it would be cool to have a different name for each of these styles. Also, there was some contractual issue. For me R&S was the first record company and after a few months, they wanted exclusivity, they wanted me to use my Ken Ishii name only for their releases, so I had to use different names when I worked with other labels.

But basically my Ken Ishii name is the one that covers everything. It can be anything from stuff that might appeal to the mainstream to more experimental or freestyle music. This is my main thing, my real attitude. And when I was doing something really different I used those different names. When I did really straightforward dance music I used FLR and released it on the Japanese label Reel Musiq and when I was doing more experimental and underground stuff, I used Flare and released it on Reel’s parent label, Sublime Records.

Sublime was a label that played a crucial role in the early developement of the Japanese techno and had a rosters of producers who all became key players of the scene later on. How did that label start and how did you get in contact with them?

It was in ’94. The same time I made my debut in ’93 was also the beginning era of Japanese techno and around ’93 / ’94 a lot of people were encouraged to try to do something by themselves and Sublime was one of them. The boss of Sublime contacted me through my DJ friends and he was really interested in having me as one of the first artists on the label, along with Susumu Yokota who, also in ’93, had some releases out on Harthouse from Germany. And Sublime was more like a proper project, not like some typical personal labels by DJs. They had crew and their own company, so I felt that they were a proper partner for doing music together. That’s why I decided to work with them and they became my most important working partners in Japan.

I always felt that those early Sublime releases by you, Yokota, Co-Fusion, Rei Harakami and the others, while obviously influenced by Western music, still had a very specific sound, that set them apart from Western artist that were doing similar music around that time. And even though those Sublime acts mostly differened a lot from each other in style, they still had that common sound, that I just could not pinpoint at that time. And I actually first heard YMO a few years later and after listening to their later releases, especially Technodelic from ’81, I felt that that’s it, it is the missing link between Western techno and the early Sublime sound. So, do you think that YMO could actually have a direct influence on the early Japanese techno producers?

I guess so, especially our generation, we were all influenced by them. As I said they very really huge in Japan and had a big impact both musically and culturally. Also, we did not have a proper rave scene or underground techno scene in Japan before us, the first generation of modern techno in Japan started to play. There was a bit of a New York style house scene with clubs, but while in Europe there was a techno scene earlier, we did not experience any of that. We were more influenced by YMO and some other bands around them, so, you are right, maybe that’s the main reason why were not typical dance DJ artists.

Which were the venues, event series and festivals that played an important role in the development of Japanese techno, that made the genre more visible for the general public and helped to bring new talents to the forefront?

The first venue that specialized in techno and other styles of early electronic music was Cave, 200/300 capacity, located in a basement of a small alley in Shibuya, Tokyo. I used to go there every weekend for the music the resident DJ Kudo played when I was a student around 1990-1992. I would say this place was where a proper techno party was born in Japan.

Then Yellow in Nishi-azabu, Tokyo, took over the residency of DJ Kudo and pushed techno and house that were starting to expand in the underground scene. They were one of the few clubs that invited international DJs regularly and kept giving people an impact in the early ’90s.

Now, this was the most important venue for upgrading techno to the mainstream. Liquid Room, in Shinjuku, Tokyo. It was definitely the center of the Japanese techno scene in the mid ’90’s to the early 2000’s, the period that techno made huge growth. It was like Tresor in Berlin or Rex in Paris. I used to play there every month along with international DJs of the time. There is Liquid Room in Ebisu now, but it’s run by a different management.

Finally, WIRE Festival was the highlight of the Japanese techno scene. Running from 1999 to 2013, this festival was something that characterized what the techno scene looks like in Japan, with a huge international and domestic lineup.

While later on, you did not really use other names with the exception of Flare, in 2012 you released an album as Metropolitan Harmonic Formulas, which had a very different sound compared to your other works, actually it was closer to downtempo..

Yes, and easy-listening.

What was the story behind that one and was that a one-off project?

Yes and it was actually made upon request from a fashion restaurant shopping complex in Roppongi, Tokyo. At that time that was the most trendy fashion complex and they approached me to some music exclusively for the department store. They wanted some original music and also a monthly DJ program, which isn’t too hard or too underground. And actually originally I had that kind of style, the Mr. Fingers sort of deep house, but as Ken Ishii I did not release that sort of music as it was too different. But still, I always wanted to do something like that, so when they approached me I thought that, now is the chance and, under a different name, but I did it.

Oh, so that’s why it was so different!

Yes, but in a way Japan is far away from European scene and there you can do several different styles. Japanese fans see me like an individual artist, they don’t label me just as a techno artist and see me more like an electronic music artist and I can work in several different styles.

You started you own label, 70Drums back in 2001, which, even though there were longer gaps, is still active today. What was your goal with the label, to release your own music that you cannot release elsewhere or is the label also open for other artists?

That label is basically for my own music, so it is not a typical dance label that releases something every week or every month. Ideally I wanted to release my own project, ideally albums on this label. But to make an album is something different from releasing EPs, doing remixes or DJing, doing an album is more conceptual, so it just needs time and motivation, so it is fine to have some gaps. At the moment I am not sure when a new album comes next, maybe something in two year, but maybe just five. As for EPs, I will release a song, when I feel like that, when I feel that I have something wouldn’t suit other labels. In 70Drums, I do not care about any trends or BPMs or whatever, I just release what I want to make as an artist.

After ’93 how fast did the Japanese techno scene started to grow?

So fast! I got more international recognition with the release of my album, Jelly Tones in late ’95 and around that time, in ’95 or ’96, we already had big outdoor techno events in Japan. So, basically within three years it was like going from 0,1% to 100%. But maybe that we, Japanese people already liked electronic music, thanks to YMO and that we had the Sublime acts, Denki Groove and other homegrown artists helped the scene to grow so fast. And from the late ’90s the local media really picked up this movement. Magazines, news papers, tv programs. I actually often went to NHK, the national tv to do some talk or to DJ. It all happened so fast.

In an older interview you said that besides other project of yours at that time, like writing music for the Nagano Winter Olympics, you also had a European rock festival tour… playing at Lowlands and the like? How did that happen?

It happened in ’96 and it was R&S who arranged the whole thing with the festivals. In ’95 and ’96 I did a lot of touring in Europe and R&S hired an English tour manager to travel with me. And basically it was him who taught me how to talk in English. I studied at school, but never actually used it, but traveling alone with an English guy for two months… I had to speak in English. As for the Olympic Game stuff, R&S at that time had a licensing deal with Sony Japan, so R&S was basically working with a major record company in Japan. So, I think the Olympic Committee gave a request to Sony Japan and the top guy there, who controlled all the media and such, directed that request to me. It was quite astonishing. I mean, in ’92 I was just a student and a few years later I was like Ryuichi Sakamoto. I still remember that the first time I received the request from Sony, I asked… “Really? Me? Not Ryuichi Sakamoto? Do you think I can do this!?” But they said that yeah, yeah, you should do it! So I did it. But it was all made in my bedroom with some tiny gear, that’s where I produced the main theme for the Olympics!

How much did your gear change over the years?

Around that time I was only using hardware and a small mixer, but later on I switched to ProTools. And while I am still using some hardware, mainly, to this day, I still use ProTools and some plugins.

How do you share your time between touring, shows in Japan and producing new music?

I have been making music for 30 years now, but luckily I still love doing it and I still love playing live. Usually I come to Europe about every two months and I also go to US, once in every two or three months, plus I play in Asian countries sometimes and play in Japan, not only in Tokyo, but in other cities as well.

But when I am in Japan and have time, I always make new music and I love doing it. I always have some deadlines to keep and I have a couple of new gear lying around, still unused, that I want to try one by one, so I need to spend some time in Japan!

Is there anything outside of music that influences or affects your music style?

When I make dance tracks, I am inspired by other people’s dance music, but when I make my own music, I mean, when I am doing something different, I listen to other kinds of music, like soundtracks, jazz, experimental or ethnic music and also, sometime I just want to feel motivated and I often go to modern art museums. It is just inspiring to see new ideas. So, these are my main influences outside dance music.

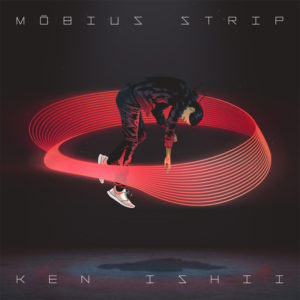

The artwork for your latest album, 2019’s Möbius Strip and some of its singles (Take No Prisoners, Green Flesh) was done my a Hungarian graffiti artist, NikonOne. How did you two came to work together? (check the artist’s Behance site for the complete Ken Ishii x NikonOne collab artowork)

He posted a photo on my Facebook in comments of a graffiti, inspired by my music video, Extra, that he has done and I responded, that “wow, that’s great, where did you do that?” And then we exchanges some messages and it gave me an idea and I told the Japanese record company I was working with that I know this graffiti artist turned graphic artist who is so good and special, so I want to use his art. And the record company said that wow, it’s great, let’s do it! So it was a really basic, down to earth sort of situation.

Photo courtesy of NikonOne.

Besides DJing, are you still doing live sets? And how different they are from your DJ sets?

I still do it, not so often though. Last time I did it was during Covid, for a live stream. Usually I want to do that when I do an album. Because when I play live, I play something that differs from my DJing, a showcase of my tracks, that does not have to be all straightforward dance music, but can have some other elements as well. But now I am thinking of doing something… maybe this year. I work with a jazz musician, a pianist, we have been working on a collaboration for the last two years and when we finish the album we will do some lives together.

Besides this, do you have other releases, EPs, remixes coming up in the near future?

Yes, the latest one is a remix for Cristian Varela, a Spanish techno veteran and… well, there are some other remixes for some others, but actually I am not quite sure what is coming out next. You know, it is because they don’t always release these as soon as they get the remixes, sometime I finish the remix and then two years go by until they are actually being released. But the main thing is definitely the collaboration album with the pianist, Masaki Sakamoto. He actually had some releases out on Sublime, both solo works and collaborations with Atom™ aka. Atom Heart, the German electronic music artist.

After the huge late ’90s boom, the Japanese techno scene remained as big as it was then or did it have its ups and downs?

Sure there were some ups and downs, but for the most part it remained stable. Some guys from the first generation like me or Takkyu Ishino are still on the scene and we have some new names too, so I think it is kind of healthy. You know, after Covid, we were really nervous, because the older crowd simply disappeared. I don’t know if it happened here as well?

Yes, to a certain extent the whole party culture changed during Covid.

Yeah same in Japan and the old crowd… they just do not come back to the scene, but now we have a new generation. A new crowd as well as new DJs and promoters, so it is a good sign.

How did Covid affect the club scene in Tokyo, were there many venues closing?

Yes, even though not all closings were due to the pandemic, but we lost three of the most important techno clubs in 2022, Ageha, Contact and Vision. We still have Womb, but other than that, the clubs that we have nowadays… well, while they are not bad, they are just not as great as those three were.

For Japanese acts from most genres, it often seems to be quite challenging to become well known outside Japan. Of course there are always some exceptions mostly from more underground genres, but besides the noise scene (and the jazz scene to a certain extent), the only music genre where Japan really became a vital part of the international scene is techno. What do you think, how the techno scene was able to make it and why is it that difficult for acts from most other genres?

What is important to know is that Japan has its own music market inside and people can become rich only working inside Japan. Japan is a small country, but it still has the second biggest music market in the world. So they don’t have to think about a career outside Japan.

Yes, but still, it is mostly true about the mainstream acts, that they just do not care about success outside Japan, because they can achieve whatever they want inside the country. For more underground acts it is not necessarily true.

Yes, but still, many can live off what they make just inside Japan. And also there is a structural problem in Japan, that most of the record companies think in yearly projects. Every year one album, then tour then it is finished. So, they tie their own artists up with their business schedules. They don’t think about selling their music outside the country.

It is mainly because Japan was a big market, but it is not anymore, it is changing now, just maybe not on the level of underground music. K-Pop is huge worldwide and lots of people really love it and some old-fashioned Japanese people, who are also present in the music industry, looked down on Korean music and culture. But nowadays they start to feel that they have to learn something from Korean culture, so, their mentality is changing. But younger generation are different, they have internet and social media, so now it is easier for them to connect outside the country and it is also easy to become known at some level, but it is hard to earn money out of it. But still, I think it is a good start for them. They have to compete with artists from other countries, but I think the young generation in Japan is realizing that this is the time to be more international.

And what do you think made techno the exception? Ever since the mid-’90s Japanese techno artists are a part of the international scene. Do you think it has to do with the language barrier not really being a problem in techno music?

Yeah and also because techno is really universal music, it is not only from English speaking countries. There are a lot of German and French producers, also Spanish, Russian, South American. And in Japan, maybe it is also because out generation, the first generation was quite open-minded, so maybe we were the good examples. We showed it to the people how easy it is to get connected to the international scene. I think in rock and other mainstream music, they always like to look up to Western music culture, they just adore it and wouldn’t try to be a part of it. Japanese are often very hesitant and reserved, but maybe techno will change the mentality of upcoming artists from Japan.

Last year you did soundtrack for Yakitori, a series on Netflix and it included some typical Ken Ishii techno tracks, but also stuff that was very different from what you usually do. Was it challenging to work on something that differs so much from your usual style?

Basically the series director of Yakitori chose me because of my music and initially he said that I do not have to change my style and only wanted me to do some key tracks and wanted to ask others to write the rest of the soundtrack. But I told him… let me do it, let me do everything and I will try learn how to write music for normal scenes. So, at the end, I took care of all the music, but I did study some other soundtracks made for films, especially Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence by Ryuichi Sakamoto. That is an old album and I haven’t listened to it in decades, but now I studied it very carefully. So it was a really big thing for me.

Are you still following the new, up-and-coming techno artist, both from Japan and elsewhere?

Yes, a lot of them.

And are there new producers that you find inspiring, that make you go “oh wow, this is something really new, really great”?

Not many, but yes. Now techno is everywhere, there are just too many releases. But still, there are ones that are not something drastically new, but still bring something new to the genre, like Vinicius Honorio from Brazil, who is probably my favorite from the last couple of years. His music has a dark and hypnotic but funky afro atmosphere. Not a style you can often hear in techno. Also, The Southern, from Italy, who puts ‘jackin” elements from old school Chicago house into modern faster and harder techno, or Hertz, a techno veteran. I play lots of tracks by him, I love his funky and percussive style and solid production. And Go Hiyama, one of the techno pioneers from Japan, who makes more experimental electronic music these days. It always gives me a fresh surprise. I collaborated with him on my album Möbius Strip in 2019.

Tonight’s party is in celebration of the 30th anniversary of your career, will it have more tracks from all over your career or how will it differ from your usual sets?

I think it will be a combination of my current DJ style with my old tracks, it covers everything from very old stuff, that are good to dance, to my latest stuff. Kind of like an anthology.

It is a bit off topic, but you work with modern technologies a lot, so.. what is your opinion about AI? In the graphic art community it worries a lot of artists that based on the art they have done over the years, AI can now generate new art with just a few clicks and keywords. So, many feel that it is pointless to learn and spend long years to become an artist when others generate the same thing with a few clicks and people and companies will just choose AI art because it is cheaper. How do you feel about this and do you think it is bound to happen to music as well sooner or later?

Well, basically I am not against new technology, because I was always following and taking advantage of new technological developments. So, I know that with visuals, not necessarily with moving pictures, but with images, AI can do a really good job, but for music, I haven’t heard any new stuff created by AI.

From what I have heard it also has to do with the lobby power of the big record companies, that they stop tech companies from releasing software that can do such things, while visual artists just do not have that kind of power.

Well, if AI will be able to make better music, I think everybody will just go there, same thing as with other sorts of technology, people always go for the cheaper, more handy solution. That’s why we artists have to keep studying and learning to be able to create something really good. And also, as a music producer, I feel that making music needs so much of a delicacy. Creating a sounds and tones. And also, mixing. It is so hard to do the right mix, I still learn how to mix. Making music, not DJ mixing. DJ Mixing too, but I am talking about mixing to make music, I still learn from Internet and I also learn new plugins, software, gears. You just have to keep learning to compete with an AI. I think that’s the key.

And what do you do, when you are not making or playing music? I’ve heard you are involved with a brewery?

Yes, making beer is something I do out of passion. I simply like craft beer and I want to make a beer that I like the most, so I want to create my own favorite recipe. So, in a way it is like making music. I want to hear my ideal music, so I make it myself, for both, that’s the basic attitude.

Is the beer available only in Japan for now?

Yes, I think importing alcohol is not that easy and needs a lot of paperwork and the part I concentrate in the brewery is making the recipe and doing labels and artwork. And apart from beer I do t-shirts, I do design by myself sometime, but also work with professional designers. And I like cooking too, I am kind of a simple guy, I do not do anything special. I like to walk around, which can be an inspiration when I see something new, also meeting good guys, telling me about history and giving tips about the city. So, that’s what I like. I want to be inspired by anything, any time.

Thanks to Deep Art and Technokunts for making this interview possible!

All live & backstage photos taken at A38, Budapest.